Addressing Disc Disease from a

Prolotherapy Standpoint

The diagnosis of “disc disease”, “bulging disc” or “disc herniation” is very common. However, many believe that ligament weakness exists before a disc herniates. It is important to understand what a disc is, the natural course of disc disease, how ligament weakness/laxity fits in, and how Prolotherapy can help.

Disc Disease Basics

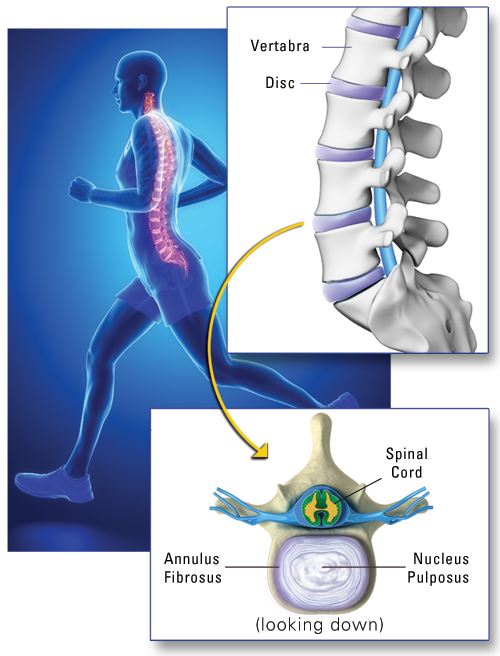

The disc is a circular, collagen-type tissue, which acts like a cushion and shock absorber between the bones (vertebrae) in the spine. The center of the disc is a jellylike, watery material called the “nucleus pulposus” (Latin for “center pulp”). The disc does not have a direct blood supply of its own, and therefore has limited healing ability. The outer portion of the disc is called the “annulus fibrosus” or simply “annulus” (Latin for “fibrous ring”); it is composed of strong, ligament-like fibers and there are nerve fibers on its outermost edge. Because the disc sits between the vertebrae, it is called an “intervertebral” disc.

Disc Degeneration

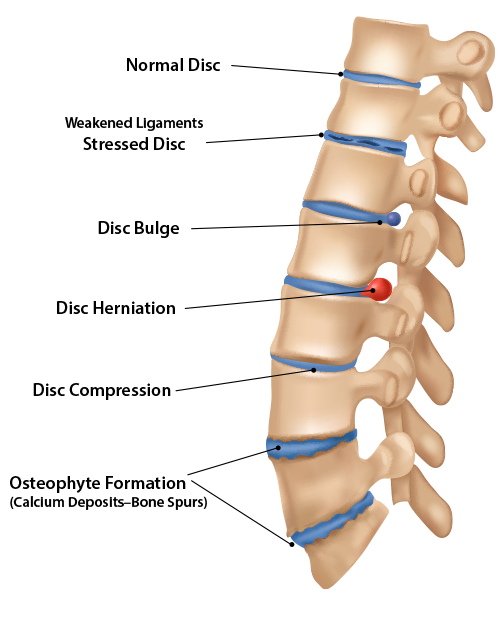

Like other parts of the body, discs experience “wear and tear” as we age. The center of the disc (the nucleus pulposus), which is 85 percent water in a young person, tends to become dehydrated over time, and may only be 65 percent water in an older person.[1] Factors which lead to disc degeneration are lifting heavy objects, excessive bending, and sitting for long periods of time, all of which can put extra strain on the discs, leading to flattening and dehydration. This usually occurs over many years with small injuries that slowly accumulate. Since discs lack direct blood supply, they cannot easily regenerate and repair themselves; once flattened, they remain so. However, the presence of disc degeneration does not necessarily mean pain, or a problem exists. In fact, disc degeneration is an MRI finding for many individuals who have no pain at all.[2] This should not be a surprise since, as discussed earlier, abnormal findings on MRI exist in pain free individuals. Disc degeneration is, in fact, so common that it is considered part of the normal aging process.[3]

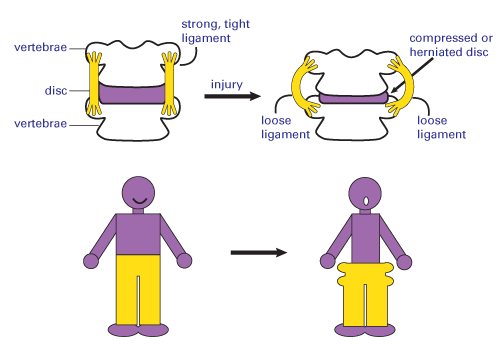

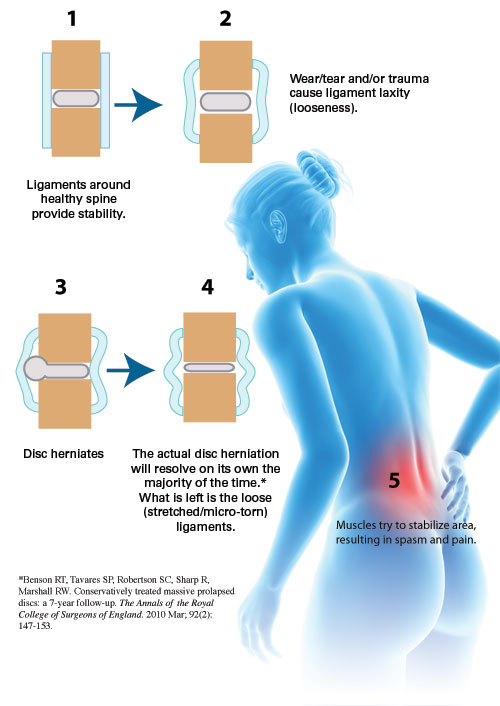

It is important to understand that for a disc to bulge or herniate, there must first be ligament weakness allowing it to do so.[4] Ligaments surround the disc and are designed to hold it securely in place. In a younger person, these ligaments fit snugly around the vertebrae and disc between them. But as a disc loses moisture and flattens over time, or as there are traumas or micro-traumas, the ligaments stretch and become lax. Imagine if you lost six inches around your waist, but didn’t tighten your belt!

Since the disc has no blood supply and cannot regenerate, a flattened disc means there is no longer a snug fit between the disc and the ligaments—in the same way that you’d be swimming in your old bigger pants after losing weight. The extra space around the disc allows excess disc and ligament motion—joint instability—leading to a disc bulge, and then, eventually, to the next stage: disc herniation.

Once a herniation occurs, the outside edges of the disc may become cracked or torn,[5] allowing the fluid in the disc’s center (the nucleus pulposus) to leak through these cracks, causing irritation. As you can imagine, this leakage also decreases disc height, resulting in further instability and a thinning disc, which in turn means more laxity of the surrounding ligaments.

Over time, and in a further effort to stabilize the continuing instability, the body starts to put hard calcium deposits (“osteophytes”, also called “bone spurs”) in that joint to stop the excess motion, and the final stage of disc disease occurs: osteoarthritis. After the first disc herniation, other discs are more likely to be affected and eventually bulge and herniate. Simply put, the ligament holds the disc in place, so if the ligament weakens, the disc can herniate through it. Increased pressure on the disc (high demand activities), together with increased ligament laxity, is the perfect recipe for further disc herniation.[6] If instability continues long enough, the result will be degenerative osteoarthritis.

The Natural Course of a Disc Herniation

When a disc first herniates, it can be painful enough to knock a person flat, so to speak, and the effects can last for several days. But this injury can heal; in a few days, or maybe a few weeks, the protruding disc segment slowly reduces in size.[7] In fact, most disc herniations resolve within two to six weeks, restoring the patient back to 90 percent of normal activity within one month, even without treatment.[8]

However, it has been estimated that 10 percent of people who suffer a disc herniation continue to have pain; usually this involves chronic muscle pain, spasm, and stiffness (a sign of ligament laxity and a weak joint). These symptoms may persist long after the disc herniation has reduced in size and is no longer causing a problem because the ligament laxity and weakness is still present.

While someone can suffer a disc herniation because of sudden or severe trauma, such as lifting something heavy, as mentioned earlier, many herniations occur over time due to repetitive trauma—some large, some small, which accumulate. There may not even be a history of back pain, but then one day a minor event, even just a cough or sneeze, is enough to trigger herniation.[9] While the innocent activity seems to be the cause, it was just the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. Over the years damage to the area has been adding up, until a person is, in a sense, sitting at the edge of a cliff, so it may not take much of a push to fall off. Most people don’t notice the slow process of disc degeneration and ligament weakening, and so may not even know there is a problem—that is, until the camel’s back breaks.

Most Disc Herniations Resolve Without Surgery

As previously mentioned, most disc herniations resolve without surgery. Two studies found no difference between the final results of surgical and nonsurgical therapy after 7 and 20 years of observation.[10] Another study found a 92 percent return-to-work rate in a group treated conservatively without surgery, even though 60 percent of those individuals initially had muscle weakness and 26 percent showed disc rupture on the CT scan.[11] A more recent analysis of multiple studies compared changes in MRI scans over a period of a year for patients with low back pain and sciatica. This review reported that up to 93 percent of herniations reduced or disappeared in size without surgery, and up to 91 percent of nerve root compressions (where the nerve is being pressed by the herniated disc) also reduced or disappeared without surgery.[12]

This explains why surgeries for disc herniations based only on an MRI may fail. The MRI may show an old remnant (small remaining piece) of a previous disc herniation that resolved on its own long before, and is not actually responsible for the patient’s current pain. Therefore, surgery addressed to that area may fail to resolve the problem. A review of 1,108 patients who, based on their MRI results, received disc surgery, found that one year later more than 50 percent of these patients were still experiencing pain.[13] Put simply, the presence of even large herniations or disc ruptures should not be taken as an absolute reason for surgery[14] While there can be emergent needs that call for surgery—such as trauma resulting in back fracture, or sudden loss of bladder or bowel function—only a very small percentage of disc herniations truly require surgery.[15] Most practitioners agree that conservative nonsurgical approaches should be recommended first.[16]

Platelet-rich Plasma for Disc Herniations

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections are a safe and effective treatment for disc herniations. Patients with MRI proven disc herniations, who also had neck or low back pain were treated with platelet-rich plasma injections in and around the joints and ligaments of the spine where the herniation was. Not only were the injections themselves safe with no complications, but eight years after these injections, 87% of these patients continued to have improvement. The authors concluded that in comparison to spinal surgery, with its higher risk and complication rate, platelet-rich plasma was an effective option and a much safer alternative.[17] This study also confirms that treatment to the spine area around the disc is an effective treatment for disc herniation.

Another approach is the direct injection of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) into the disc. This would be done in those less common cases of low back pain where there is a high certainty that pain is being generated from the disc itself (“discogenic” pain).[18] Studies have had encouraging results,[19] however are still ongoing.[20] Small investigations into the use of bone marrow concentrate[21] or adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells[22] injected directly into the disc have also been promising, although additional studies are still needed.[23]

How Prolotherapy Regenerative Medicine Helps Disc Disease

There are two very important points to remember about disc disease: 1) Disc herniation is almost always a result of ligament weakness/laxity, and, 2) The majority of disc herniations resolve on their own without surgery. When pain continues, it is usually because the reason for the herniation—weakness of the ligaments supporting the disc—has not resolved or been addressed. The pain also comes from muscular spasm, which is how the body’s tries to stabilize the weakness. This muscle spasm can last long after the disc has healed.

Prolotherapy helps these issues by stimulating repair and strengthening of weakened ligaments around the disc and in the region, making the joints stronger, reducing or eliminating pain.