Osteoarthritis - Degenerative Joint Disease,

Regenerative Medicine Can Help

“Arthritis” is a diagnosis frequently given to a patient as the reason for his or her joint pain. The word itself comes from arthr, meaning “joint,” and itis, meaning “inflammation.” There are several different types of arthritis, the most common being osteoarthritis (abbreviated “OA”)[1] (osteo for “bone”). OA is also known as “degenerative joint disease” or “wear-and-tear” arthritis. OA is diagnosed when bony spurs, calcium deposits, and/or cartilage breakdown appear in an X-ray or other imaging of a joint.

Typical medical recommendations for OA are pain medication or NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), which offer short-term relief but, as discussed earlier, may have unwanted side effects. Cortisone injections are also often recommended, which may sometimes help temporarily; however, they can have adverse effects on joints and joint tissue. Hyaluronic acid (a jelly-like substance that provides padding) may help, but only temporarily. More hands-on approaches such as physical therapy or osteopathic or chiropractic treatments may help, but not in every case. And, of course, there is surgery, which may not be clear-cut as to need, has additional risk, and may fail. Clearly, there is a need for a safe and effective nonsurgical treatment for OA. Fortunately, we have Prolotherapy Regenerative Therapies. To understand how Prolotherapy helps with OA, it is important to understand how and why OA develops.

Joint Instability: A Common Cause of Osteoarthritis

Unresolved ligament injury results in ligament looseness (laxity) and joint instability, which then ultimately leads to abnormal loading of that joint, uneven wear and tear, and eventually OA.[2] This is seen in athletes who suffer ligament or tendon injuries, then later are seen to have OA.[3] In fact, insufficient healing and weakness of ligament or tendon connective tissue supporting a joint is believed to be one of the most important factors in the later development of OA.[4] Therefore, OA is, in most cases, a result of the problem—connective tissue weakness—rather than the cause.

Ligament Injury Precedes Osteoarthritis

As early as 1972, researchers noticed this relationship between ligament injury, joint instability and the later development of OA.[5] A very large, well done study investigated this relationship by seeing what happens to a particular joint in the hand over time. Patients were seen for 25 years, interviewed as to pain or issues, examined for stability, and received regular hand X-rays to see the condition of that joint. At the beginning of the study, these joints were stable and there was no OA seen in the joint. What was noted, over the years, is that the first thing which occurred was ligament weakness, followed by joint instability—long before any signs of OA in X-rays.[6] In 2006, a similar study was done, using MRI, with the same conclusion, that ligament injury occurred before any OA or cartilage defects developed. This resulted in the conclusion that ligament and tendon injuries “have a central role” in the development of osteoarthritis, a conclusion now shared by many other researchers.[7] It also appears that the more severe the ligament injury is, the more severe the progression of OA.[8]

Osteoarthritis (OA) is often diagnosed from an X-ray, which identifies bony deposits. Many people have these types of calcium deposits on their X-ray images, without necessarily noticing any pain or symptoms. However, for others, OA progresses and may result in restricted movement and pain. You see, the calcium spurring creates an irregular stress and wear pattern on the joint surface (especially load bearing joints such as knees and hips), which can eventually break down protective cartilage. This uneven stress on the joint will then stimulate even more calcium spurring and OA because of Wolff’s law (named after Dr. Julius Wolff) which states “Bones respond to stress by making new bone.”[9] Therefore, the presence of OA in a joint, over time, has a tendency to worsen the degeneration and OA in that joint.

As you can see, osteoarthritis is not just a disease of cartilage breakdown, as many people believe, but rather one of connective tissue instability.[10] And there is a direct relationship between connective tissue injury, joint instability and the later development and progression of OA”[11]

Studies confirm this relationship. For instance, a very high percentage of female soccer players with knee ligament injuries were found to knee OA 12 years later.[12] And there is an increased incidence of OA in individuals who have played certain sports, known to be hard on connective tissue, such as wrestlers, boxers, baseball pitchers, cyclists, football players, weightlifters, and others.[13]

Surgery for Osteoarthritis

If OA gets severe enough, it may eventually affect joint structure and function—causing both restriction in range of motion and continual pain. In those very severe cases, surgery may be needed. This is especially true with hips, which are by far the least forgiving joint when it comes to OA. However, as noted previously, abnormalities such as OA exist on imaging studies in pain free individuals.[14] Or, if pain is present, it may be the result of the connective tissue injury which caused the OA, rather than the OA itself. Therefore, the presence of OA alone does not necessarily indicate that a surgical procedure is called for.

In May 2016, Orthopedics Today reported on a study in which nearly 40 percent of 272 patients “reported persistent knee pain” one year after total knee replacement surgery.[15] But in a way, this makes perfect sense: since knee replacements do not treat connective tissue injury, pain and instability coming from these tissues remain, even after knee replacement.[16] In other words, although a symptom (the OAOA question whether surgery is always the best answer.[17] The current recommendation by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons is that knee replacement be reserved for only the most severe cases and then only after nonsurgical management has failed.[18]

A less invasive type of surgical procedure, arthroscopy, has also been widely used to treat OA of the knee for many years. Surgical procedures were done to “clean out” the joint using this method. However, scientific evidence to support this as an effective treatment has been lacking. A very famous study done and published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2002 asked the question whether surgical intervention for knee OA (“cleaning up” the joint) was worthwhile. The study involved three groups. One group of patients received an actual arthroscopic “cleanup” procedure; the second group received a slightly more aggressive “cleanup” and clipping procedure; the third group received only a “placebo” procedure that involved going through the motions of being taken to the operating room, an incision made, etc., but without the actual procedure being done. This was a double-blind study, which meant that neither the patients nor the doctors doing follow-up knew which patients had received the actual, versus the placebo, procedures. After two years, the study concluded that outcomes with the actual procedures were no better than those with the placebo, and at some points during follow-up, results were worse in the actual treatment group.[19] A repeat of this study published similar results in 2008.[20] And a 2013 study evaluating arthroscopic surgery for degenerative meniscal tears produced similar results: showing no advantage of surgery for these conditions.

The presence of OA alone does not necessarily indicate that a surgical procedure is called for.

In other words, a large number of people have undergone surgical procedures for OA based on an X-ray or MRI that didn’t necessarily provide the benefit that was needed. And if this weren’t bad enough, remember that any surgery to a joint can be aggravating, potentially promoting, or even accelerating, OA! Patients receiving even minimally invasive knee arthroscopy were found to have three times the risk that future knee replacement would be needed.[21] And those receiving a larger surgery involving the meniscus had a 10 to 18 times likelihood that OA would develop.[22] Therefore in 2017, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons published a strong recommendation against the use of arthroscopy in nearly all patients with degenerative knee disease.

Fortunately, Prolotherapy has been shown to be effective in stimulating connective tissue repair, stabilizing the joint, and preventing further OA. However, if the “horse is already out of the barn,” and OA has already progressed to the point where it is part of the reason for the pain, Prolotherapy has also been shown to be effective in stimulating cartilage regeneration, discussed further in the study summaries that follow.

Published Scientific Studies and Research Supporting Prolotherapy

for Osteoarthritis

Traditional Dextrose Prolotherapy Studies

Multiple investigations[23] have demonstrated that Dextrose Prolotherapy effectively reduces OA pain[24] and stimulates cartilage regeneration.[25] Improvement in cartilage has been verified both with X-ray[26] and tissue biopsies before, and after a Prolotherapy treatment course.[27] Patients receiving Dextrose Prolotherapy have also been found to be better when compared to patients receiving traditional arthritis treatments when evaluated six months later.[28]

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Prolotherapy Studies

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) for OA has been extensively studied, especially for knee OA and conclusions are that it may indeed be an effective option.[29], An analysis of 1,543 patients who received platelet-rich plasma injections concluded that PRP improves function and pain in patients with knee joint cartilage degeneration more effectively than hyaluronic acid (a popular traditional treatment).[30] Another analysis of 1,423 patients showed that PRP was more effective for knee OA than not only hyaluronic acid, but also more effective than ozone or corticosteroids (other popular treatments).[31] Multiple studies demonstrate a reduction in knee pain[32] after as little as three PRP treatments, with a 2017 study showing pain reduction after just one treatment.[33]

Although the knee joint has been the most studied, other joints have been found to receive benefit from PRP treatment. When used in the ankle, it was found to improve pain, cartilage[34] and potentially prevent the need for surgery.[35] PRP injections into the hip have be shown to improve function and quality-of-life.[36] And for the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), PRP showed pain reduction and increased mouth opening at one-year follow-up.[37]

Some of these PRP studies have concluded that only those patients with early arthritis and lower degrees of degeneration had good benefits from platelet-rich plasma injections;[38] however, that conclusion does not tell the whole story. Obviously, the more advanced a patient’s condition, the more treatment is needed, but studies by their very nature have to give every patient identical treatment, and they tend to be limited to just a small number of treatments, usually just one or two. However, it has been found that a series of platelet-rich plasma injections given over time give better results than a single treatment for OA.[39] Also, protocols in these types of studies do not typically include injections of joint connective tissue; rather, they are usually just an injection into the joint. In real clinical practice, Prolotherapy treatment plans (number of treatments, intervals, aggressiveness) are customized for the specific condition of the patient[40] and usually include injections into the connective tissue attachments around the joint. The good news is that many patients with more advanced arthritis and greater degrees of degeneration have benefited when given more aggressive PRP Prolotherapy treatments targeted to, and customized for, the severity of the condition for that specific patient.

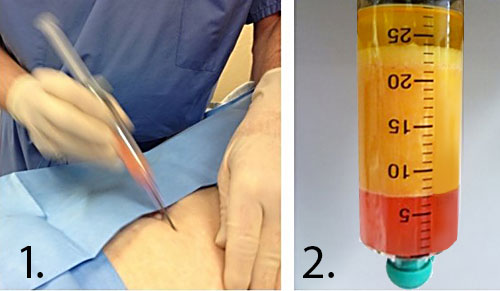

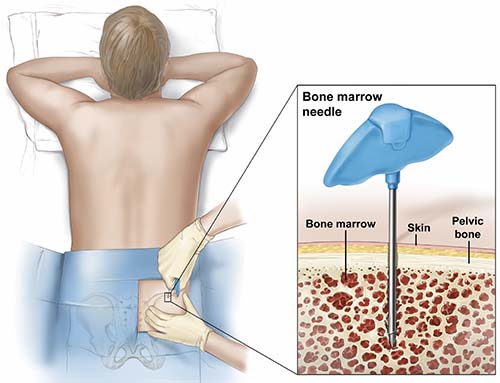

Biocellular (Stem Cell-Rich) Prolotherapy Studies

Studies using both bone marrow[41] and adipose[42] have confirmed that such treatments can stimulate cartilage repair while also slowing the progression of OA and cartilage disease. Even with more advanced OA, Biocellular treatments have been shown to be successful. In a study of severe knee OA treated with adipose, 100 percent of patients showed significantly improved joint function and increased cartilage thickness (verified by MRI), eight months after treatment. In addition, zero side effects or complications were noted.[43]

Another report showed MRI documented improvement in joint space and cartilage six months after an adipose-derived injection.[44]

Adipose-derived Biocellular Prolotherapy lends itself very well to treatment of the knee because of the fat pad located there (for more detail about this see Biocellular Prolotherapy: The Advantage of Adipose-Derived Biocellular Prolotherapy for Knee Osteoarthritis: The Fat Pad.) In fact, just transferring fat into the fat pad has been found to be an effective treatment for knee OA.[45] You may also recall that adipose has been found to retain its regenerative abilities better than bone marrow as an individual ages.[46] A study of patients 65 years old or older with knee OA showed adipose-derived cells were found to be very effective in cartilage healing, reduction of pain, and improved function, with 87.5 percent of these patients showing improved cartilage status on arthroscopic examination.[47] Increased cartilage thickness after knee treatment with adipose was verified by MRI in other studies,[48] and a review of 11 additional adipose studies concluded it was safe and effective.[49]

Bone marrow studies also show good results. 102 patients treated with bone marrow for symptomatic shoulder joint OA and/or rotator cuff tears showed “substantial symptomatic and functional improvement” as soon as one month after treatment which was sustained until the final follow-up exam two years later.[50] Bone marrow also has been shown effective in other joints.[51]

Microfracture versus Biocellular Prolotherapy for Cartilage Repair

A surgical treatment used for OA since the 1970s is “microfracture,” a technique which irritates the bone surface to try to stimulate cartilage to grow. However, microfracture has mixed, often unsatisfactory, long-term results.[52] Articular cartilage (the smooth, white tissue that covers the ends of bones, allowing the joint to move smoothly) has a very limited ability to repair itself—or to be repaired with surgical interventions—because of its lack of blood supply. A 2013 study compared two groups of patients over the age of 50 with ankle cartilage lesions. One group received only microfracture; the other group received microfracture along with an injection of bone marrow–derived cells. The study concluded that there was “significantly greater improvement” in the group that also received the bone marrow injection.[53]

Osteoarthritis appearance on imaging studies after Prolotherapy

It is important to understand that while visual improvement in the quality of the fat pad, as well as the tendons and ligaments which were treated can usually be observed via ultrasound over a period of months, the many bony deposits an osteoarthritic joint surface may not appear to change much. Over a longer period of time, increased joint space may be noticed on imaging studies, however in most joints with OA there is such a large number of bony spurs and calcium deposits that being able to perceive small, slow improvement of the bony surface is difficult. It is important to understand, however, that positive changes may be occurring nonetheless. This is made clear by an interesting case report. There, a large, isolated calcium spur is clearly seen on a shoulder X-ray within a rotator cuff tendon. Three platelet-rich plasma treatments were given to this patient’s rotator cuff tendon, and a year later another X-ray was done, showing that the large calcium spur was now gone![54] (See Figure 1: Calcium spur in a tendon before and after platelet-rich plasma).

This is significant in that it demonstrates the potential of regenerative treatments such as platelet-rich plasma to improve calcified areas. Since it was just one isolated calcium spur, the improvement can be easily seen. In areas with a large number of calcifications, it is logical to assume that there are small improvements which, while not easily seen, are nonetheless occurring. Remember that even a small difference in a body can result in a big change in outcome; for instance, a bullet could miss a vital structure in the body by a few millimeters, and the patient could live or die. So even small changes in the surface of an osteoarthritic joint may result in a huge clinical benefit, even if the image of the joint surface itself does not seem to change.

How Prolotherapy Regenerative Medicine Helps Osteoarthritis

Prolotherapy treats one of the most common causes of OA—connective tissue injury/laxity and joint instability—by promoting strengthening and repair of those tissues, stabilizing the joint and potentially preventing further OA. There is also evidence that all three formulas used in Prolotherapy treatment can stimulate the regeneration of cartilage,[55] especially the more advanced formulas. In brief, in a high percentage of patients with OA treated with Prolotherapy, the result is that the joint and surrounding connective tissue becomes stronger, function improves, and pain diminishes or resolves.