The Importance of a Correct Diagnosis

Obtaining the correct diagnosis for a patient’s pain is extremely important in determining the best treatment options. This cannot be stressed enough. Very often, patients come in telling me, “Doctor, I have a herniated disc. That’s why I have this back pain,” or, “My knee hurts because I have a torn meniscus.” They identify the cause of their pain based on the results of an imaging study such as an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan. As it turns out, and as discussed below, while an MRI does provide information, it doesn’t tell the whole story.

MRIs can be misleading in diagnosing musculoskeletal pain

The simple truth is that abnormalities that show up in an MRI or X-ray could have occurred at some point in the past and may not be the source of a person’s current pain. For example, let’s say an MRI reveals a disc bulge. Sure, that bulge exists, but it is possible that the bulge already existed before the patient experienced any pain. The only way to know how long an abnormality has been present would be if the area had been scanned previously several times over the years, which is rare in a healthy person. In fact, a large number of studies have documented that individuals experiencing no pain can have abnormal MRI findings.[1] A well-known study published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that out of 98 pain free people, 64 percent had abnormal back scans.[2] These were people with no pain! Many other studies have shown this same thing: abnormal findings exist in people with no pain. Shoulder rotator cuff tears and other shoulder abnormalities exist in MRIs for people with no pain or symptoms (medically referred to as “asymptomatic”),[3] including professional baseball pitchers.[4] Abnormal neck MRIs have also been found in asymptomatic individuals in multiple studies,[5] as well as abnormal knee MRIs in asymptomatic patients,[6] including in asymptomatic athletes.[7]

Another study looked at the value of MRIs in the treatment of knee injuries and concluded, “Overall, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI} diagnoses added little guidance to patient management and at times provided spurious [false] information.”[8] Therefore, one cannot assume when evaluating someone with musculoskeletal pain that an abnormality that appears on an MRI is automatically the cause of a person’s pain. If every irregularity revealed in an MRI were the true cause of a person’s pain, every surgery performed because of an MRI would result in a cure, but this is of course not the case.

On the other end of the spectrum, sometimes with musculoskeletal pain, X-rays or MRIs are negative or inconclusive and blood tests are normal. Yet the pain is real. There is a problem; it’s just that the results, medical tests, and scans may not reflect a reason. Therefore, the physician has to go deeper into the history, or use other tools, such as diagnostic ultrasound, to arrive at a diagnosis. To determine the cause of a patient’s pain accurately, it is very important to understand what happened prior to the problem starting, and other aspects of the pain pattern to determine a possible origin. An imaging study should only supplement—not replace—a diagnosis based on how the problem started, symptom progression, and pain pattern.

An abnormal MRI does not necessarily mean surgery is needed

As discussed above, abnormal MRIs in healthy individuals are common. Therefore, it should be obvious that an abnormal MRI does not necessarily mean surgery is needed. To further clarify this relationship, a study was done of elite overhead athletes—those who perform repetitive “overhead” activity, such as in tennis, swimming, baseball throwing, and above-shoulder, weight-training exercises. These are athletes who are more likely to suffer injuries to their shoulders because of continual and repetitive use. At the study’s start, none of the athletes had any shoulder pain or problems, yet 40 percent showed partial or full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff on their MRIs, and an additional 20 percent showed other shoulder abnormalities. The study then followed these athletes for five years. After five years, none of the athletes interviewed had any complaints and had not needed any evaluation, treatment or surgery for shoulder-related problems during the five previous years. The study’s authors concluded, “MRIs alone should not be used as a basis for operative intervention.”[9]

Diagnostic Ultrasound use in Prolotherapy

A huge advancement in musculoskeletal medicine is the use of diagnostic ultrasound imaging.

A doctor can use diagnostic ultrasound machines in his/her office to almost immediately see what’s going on in painful ligaments, tendons, and joints. This advancement not only improves diagnosis; ultrasound guidance can also help the doctor accurately place injections, improving results. Ultrasound diagnosis for musculoskeletal complaints has an advantage over MRI for several reasons. First, it can provide current, real time, information about a patient’s problem. It be performed in an office setting where the doctor can immediately and precisely examine the site of injury or pain. Also, while MRI is done with the joint motionless, some connective tissue tears do not show up completely, or at all, unless the joint is moving.[10]

Ultrasound is able to image joints “dynamically”—i.e., with movement—to see what happens to the tissue or joint. Ultrasound can also detect fluid in a joint and provide precise needle guidance in draining that fluid, or injection guidance for specific injury sites. Ultrasound can also offer a comparison between both sides of a patient—for instance, a patient’s injured right knee and healthy left knee. Such differences are often very helpful in diagnosis, but seldom would a doctor order an MRI of the “good” side. Also of benefit is the ability to compare different ultrasound scans over a course of treatment in order to assess progress over time. And, finally, ultrasound can be performed on any patient, including one who has metal in a joint—something that is not always possible with MRI, since magnetic resonance imaging machines use magnets, and may not be safe for some patients.

Color Sonoelastography

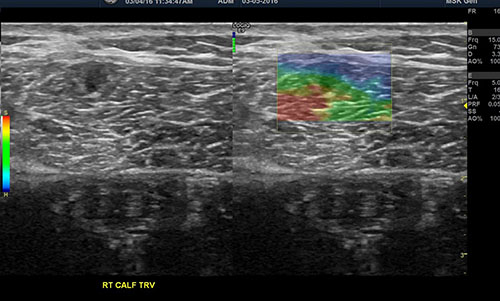

The most recent advancement in ultrasound technology is color “elastography”—also known as “sonoelastography.” “Sono” is another term for ultrasound, and “elastography” describes the elasticity or density, measured as “hardness” or “softness”, of tissue.[11] Ultrasound elastography has been used for many years to help doctors in diagnosing tumors since tumors are harder than the surrounding tissue. In the last several years, it has emerged as a useful tool in musculoskeletal medicine as another potential diagnostic tool to help detect early or small ligament, tendon, and muscle tears and weaknesses which would not otherwise be easily seen via either MRI or greyscale ultrasound. Color sonoelastography can also be used to help monitor improving tissue density over a course of treatment. There is a scale of tissue “softness” to “hardness” which shows up in colors ranging from red to blue. Tears show up as “softer” simply because the tissue is weaker and less dense than the surrounding stronger, “harder,” healthy tissue.

Figure 1: Sonoelastogram showing a small muscle tear which did not show up in MRI or regular greyscale ultrasound. [Note the muscle tear (red area) seen on the right (color) side. This is an image done on a 20-year-old runner who had persistent calf pain with activity. PRP Prolotherapy directed to the tear (red area) resolved this patient’s pain.]

A large study done in 2015 evaluated 214 patients who had symptoms (including pain) of an injured tendon, but whose grayscale ultrasounds were negative or inconclusive. In 75 to 80 percent of these patients, a defect correlating to the patient’s pain location was found on the color sonoelastogram. The authors concluded, “Sonoelastography can reveal tendon abnormalities of clinical relevance in a high percentage of cases, where the [black-and-white] ultrasound exam was negative, making the method a complementary tool to ultrasound evaluation.”[12]