Prolotherapy Basics - Change Comes from Within!

Prolotherapy is based on a very simple principle: the body has the capacity to heal itself.

Let’s say you get a paper cut. You first notice there is a rip in your skin and a little blood. Then the wound stops bleeding; it gets a little red and sore, but within a few days it has healed. This example illustrates a stimulus-response system: you injure yourself (stimulus), which sets in motion a cascade of actions that result in healing (response). A healthy body routinely and automatically responds in this way—like a computer with “healing programs” installed.

With musculoskeletal and joint injuries, a similar “stimulus-response” process occurs. However, the healing time is much longer than with a simple paper cut, lasting weeks to months rather than days. Another difference is that, even for a healthy person, the body tends not to heal 100 percent from ligament, tendon, and joint injuries. In fact, it has been estimated that the usual best result of a ligament or tendon (connective tissue) repair cycle may be as little as 50 to 60 percent of preinjury strength.[1] To understand how Prolotherapy can help heal such unresolved injuries, it is important to understand some basics about the musculoskeletal system.

Prolotherapy 101

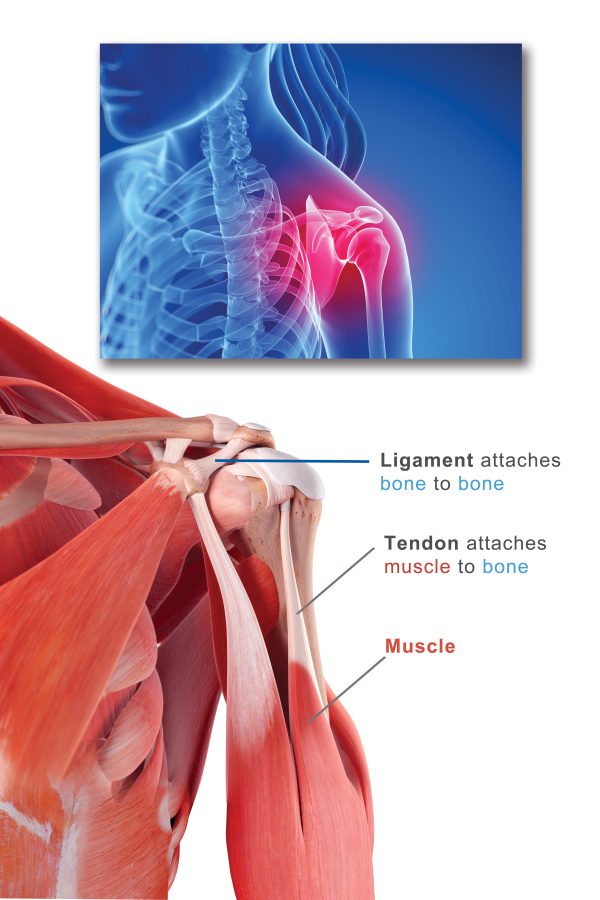

Looking at the illustration locate the red muscle on the arm. The whitish portion of the muscle is the tendon; it attaches muscles to bones. Notice that bones are connected to other bones by ligaments, which, like tendons, are composed of strong collagen fibers and are whitish in color. Ligaments and tendons are known as “connective tissue” because they connect the body’s framework of bones, providing stability and allowing for motion.

Looking again at this picture, answer these basic questions:

Question: Why do you think muscles appear red in color, while ligaments and tendons appear whitish? (If you’re not sure, consider this: What might make muscles appear red?)

Answer: Blood!

Your body needs blood to heal. Blood brings oxygen, nutrition, healing factors and cells to injured areas. Unfortunately, there is only a very small blood supply in ligaments and tendons, hence their whitish color. This also explains why a ligament or tendon injury takes a longer time to heal, once injured, than other areas of the body.

Question: Imagine someone has badly twisted and sprained his/her ankle (a sprain is overstretching or tearing of a ligament). What does that ankle look like an hour after being sprained

Answer: Swollen! You may even recall this happening if you have ever sprained an ankle. This is the body’s immediate response to a ligament injury. A signal is sent to the brain: “Send blood!”, since the ligament doesn’t have much and needs it to heal. This injury has created a “stimulus,” which then starts the “response” of healing. The body immediately tries to get blood to the area as a first response to begin repair, thus the swelling. This is also known as a “good inflammation.”

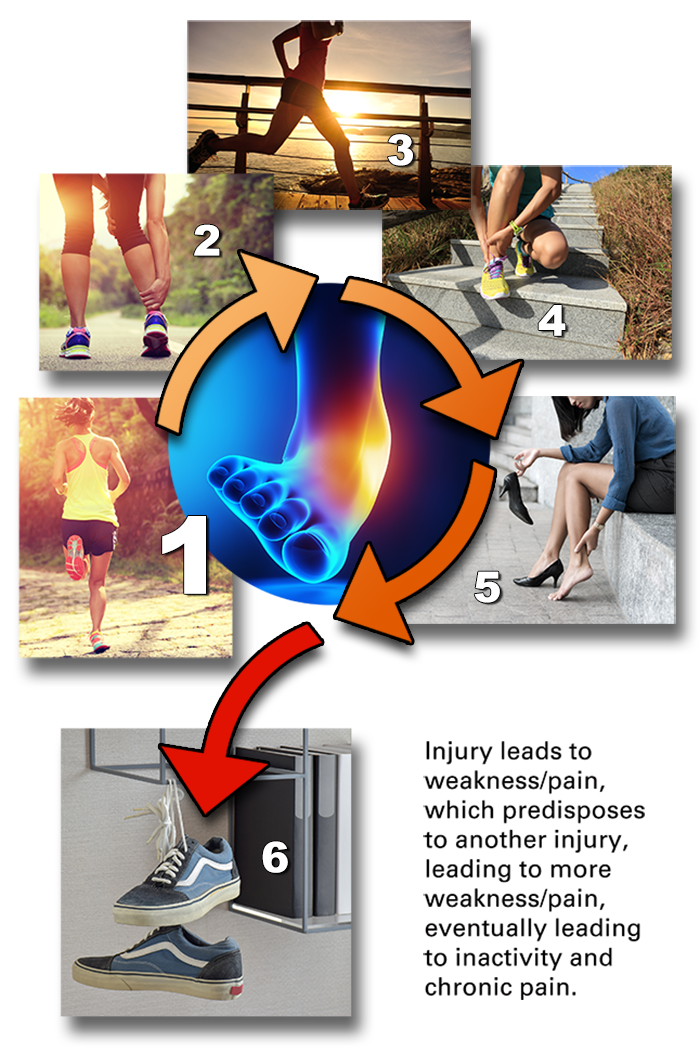

A person may experience this laxity as weakness or instability in the joint—and eventually as pain. If this happens enough times, or is severe enough, weakness, instability, and/or pain can become chronic, meaning the pain or instability does not go away even after several weeks. Note that injuries may be “acute”, meaning occurring suddenly with rapid progression, then improve after going through a connective healing period of six weeks. These injuries can also become “chronic”, meaning if healing is incomplete, or there are repeated acute injuries which do not heal completely, the pain may not go away. Note that the medical definition of chronic is “persistent or long lasting”, usually more than three months.[3]

Even disc herniations have been linked to connective tissue weakness. As early as 1952, Dr. P. H. Newman, a British surgeon with years of experience performing disc operations, concluded that torn or weakened ligaments around the spine preceded disc herniations, sometimes years in advance.[4] Dr. Newman believed the most common cause of chronic low back pain was strain in the spine area where ligaments had been weakened.[5]

The Vicious Cycle of Connective Tissue Injury

Ligaments and tendons are connective tissue composed of fibers—including collagen, a very strong protein—the purpose of which is primarily to provide strength to the joint connections. Therefore, while there is some flexibility, that flexibility has limits. Think about pulling on a rope; you can stretch it a little, but if you twist and pull it in unusual directions, or pull too hard, it will start to fray and eventually tear. Connective tissue can be overstretched, and sometimes this occurs gradually, as in repetitive motion injury, or all at once. If the injury is very severe, and the tendon or ligament has ruptured or been pulled off the bone, surgery may be needed. However that is rare, and, in most cases, the ligament or tendon has simply become lax (overstretched), with tears or micro-tears that have accumulated and not healed, resulting in weakness and eventually chronic pain.[6]

Unfortunately, the onset of chronic pain and weakness may start to limit the activities of an otherwise active or athletic person. This can be sudden, or it can be slow and progressive, until one day the individual finds that he/she can no longer participate in accustomed activities or sports without pain and may even give them up.

How Prolotherapy Regenerative Medicine Works

As discussed previously, the term Prolotherapy is short for “proliferation therapy,” so named because it stimulates the proliferation (growth) and regeneration of injured ligaments, tendons, and joints. The body, like a very sophisticated computer, has the programming in place to heal; it just needs to be stimulated in that direction. Remember, after the typical four to six week healing cycle that connective tissue goes through when injured, the stimulus to heal is very small or gone. Prolotherapy is designed to be a stimulus that starts the healing response up again. In fact, you could say that Prolotherapy “tricks” the body into into thinking it's injured again, beginning a new, strong and directed healing cycle for injuries that have not healed on their own.

Here’s how it works. A trained medical practitioner injects a natural solution (either dextrose, platelet-rich plasma, or stem cell-rich sources taken from your own body) precisely at the site of an injury. Even though these substances are natural, their introduction into connective tissue or joints is irritating and triggers a strong healing response.

Prolotherapy Formulas

Bibliography

[1] Andriacchi T, Sabiston P, DeHaven K, Dahners L, Woo S, Frank C, Oakes B, Brand R, Lewis J. Ligament: Injury and repair. In Injury and Repair of the Musculoskeletal Soft Tissues (pp. 103–128). Park Ridge, Illinois: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 1988.

[2] Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. Tendons and ligaments-an overview. Histology and Histopathology. 1997; 12(4): 1135–1144.

[3] Medical definition of “chronic.” Medicine Net.com [cited 2022 March 20]. medicinenet.com

[4] Hackett GS, Henderson DG. Joint stabilization: An experimental, histologic study with comments on the clinical application in ligament proliferation. American Journal of Surgery. 1955; 80: 968–973; Alpers B.J. The problem of sciatica. Medical Clinics of North America. 1953; 37: 503.

[5] Hackett GS, Hemwall GA, Montgomery GA. In Ligament and Tendon Relaxation Treated by Prolotherapy, 5th ed. (p. 9). Commenting on work of Newman PH. Oak Brook, Illinois: Institute in Basic Life Principles, 1991.

[6] Reeves KD. Prolotherapy: Basic science, clinical studies and technique. In Pain Procedures in Clinical Practice, 2nd Edition (pp. 172–190). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Hanley and Belfus, 2000.

[7] Reeves KD, Fullerton BD, Topol G. Evidence-based regenerative injection therapy (prolotherapy) in sports medicine. In The Sports Medicine Resource Manual (p. 611–619). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders (Elsevier), 2008.